![]() |

| The proclamation of the Republic on the Plaza de España, February 1936 |

Since I’ve been writing about the history of Vejer, people have often asked me for information about what happened here in the Civil War (1936-1939). After Franco died, most Spanish people preferred to concentrate on building a new, democratic nation, and avoided dwelling on the past. In recent years, however, a new generation has insisted on knowing more about their grandparents' war.

The facts are fairly simple. On July 18th 1936, General Franco’s Nationalist followers instigated a rebellion again the elected Republican government. The cities of Cadiz and Seville declared their support for the Nationalist rebels. The government retained control of Málaga, Jaen and Almería. Control of the smaller towns east of Cadiz, including Vejer, was established over the following few days.

![]() |

| Bernabé Muñoz Brenes of Conil, one of the many who disappeared during the Civil War |

Writing in the early 1970s, with the Francoist régime still in place, though in its last throes, Antonio Morillo’s poetic history ‘Vejer de la Frontera y su comarca: aportaciones a su historia’ (1974) is magnificently informative about many aspects of local history. Morillo believed that ‘the knowledge of history is currently a desire awakened more in the visitor than in the resident’. He stated that ‘the history of Vejer and its surroundings is a simple and straightforward story’, but bemoaned the loss of important records ‘owing to the ignorance and carelessness of past generations’.

Morillo, who became Vejer’s Mayor and remained in office for many years, wrote an evocative description of the events surrounding Vejer’s subjection by Nationalist forces. What follows is a translation of his account:

‘In the first months of 1936, the situation was chaotic. The elections of February, with the triumph of the National Front, hardened opinions on both sides. Quarrels were threatened between the parties in the coalition. The atmosphere breathed menace. On April 14th, 40 people from Vejer and Barbate were imprisoned in Chiclana, though fortunately they were set free within a short space of time.

‘Passions began to overflow on 18th and 19th July, when the first alarming news was received of an invasion from Morocco. Groups of people armed with sticks and stones began to gather on the streets, breaking windows and terrifying the people trapped inside. Fear and distress prevailed as everyone braced themselves for worse violence.

![]() |

| The hated Guardia Civil, a paramilitary police force which enforced Nationalist control |

‘At dawn that Sunday, the first bell rang for Mass. As the sound died away, several men entered the church. As the priest began the service, they demanded to search the church for hidden weapons. Don Angel Caballero tried to persuade them at least to allow the mass to be concluded, but they did not consent and the church was closed.

‘The following night, the priests and the sacristan were imprisoned in the town jail, and a heated debate was held about which to burn - the church or the houses of the rich. The first was decided upon. That same night, the altars were sacked and defiled, the parochial archives thrown out onto the street, sacred statues flung onto the floor and images torn up in the street. A bonfire was lit to burn it all.

‘The church of Vejer was a sad sight, with its magnificent images and works of art destroyed, including many antique paintings like the priceless ‘Virgen de Gracia’, along with ornaments, gilding and all the books in the archive. Everything was lost in the flames. ‘It’s been a busy night’, as some commentators remarked, emerging sweating from the ransacked church.

‘It was a doleful picture, which, out of respect and shame, I will not dwell on in all its details. In telling this history, I prefer to take the position of a bystander, and not to allow opinion to cloud the facts. But it was a degrading spectacle and leaving ideology aside - religious ones included - works of art always deserve respect. They are not the property of any time or place and under no circumstances should they be destroyed. The same goes for the archives, an authentic amassing of history over centuries, destroyed for the sake of the resentments of a single moment in history.

‘Once the burning was over, a meeting was held in the usual place, the patio San Francisco. The most enthusiastic participants wanted to continue with the looting, but Don García Pérez, the local head of the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT), managed to calm the crowd down, assuring them that they had achieved their objectives, and they returned to their houses.

![]() |

| Falangist women collecting cigarettes for Nationalist rebel fighters |

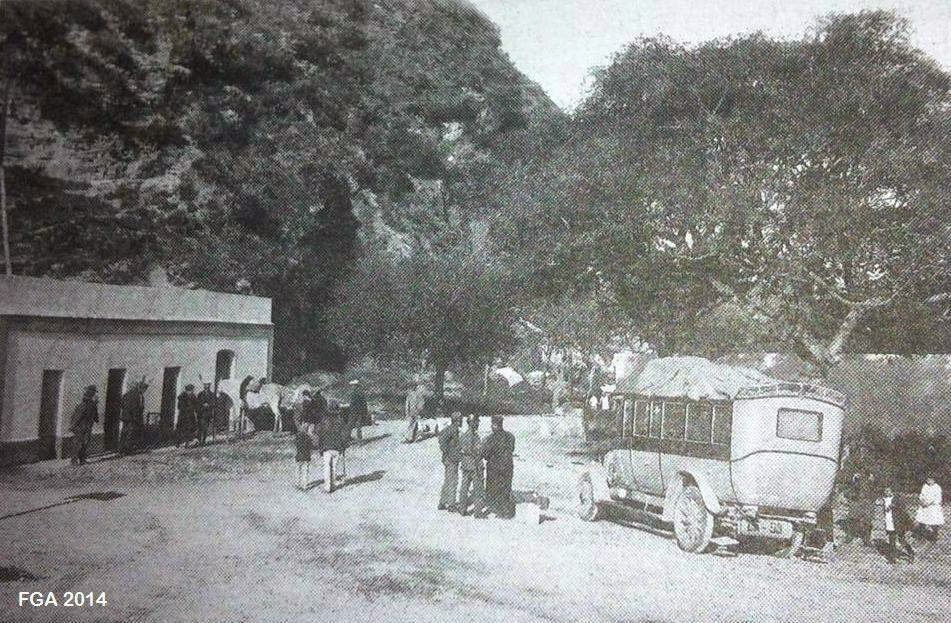

‘The following day, even the nuns joined in ringing the bells when, from the bell tower came the shout ‘¡the Moors, the Moors!’ Thanks to a telephone operator from Vejer, news of the conflagration in the church had reached Cádiz.

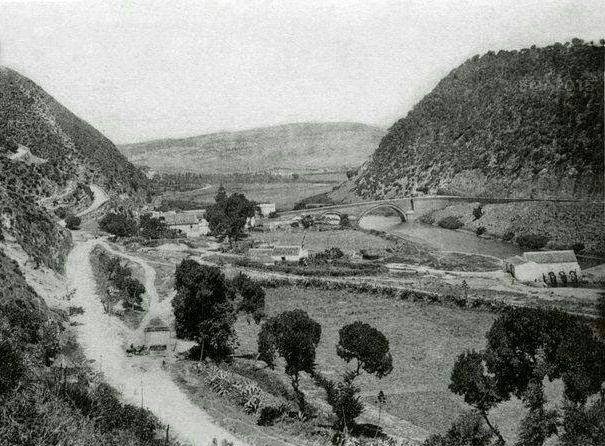

‘A lorry had been sent immediately with twenty four Moroccans soldiers, which at the command of the lieutenant of the regulars, drove up the hill towards Los Remedios. However, anticipating their arrival, the extremists had felled a giant Eucalyptus tree across the road and the way was blocked. The soldiers turned around and ascended via San Miguel. They arrived in warlike mode, commencing their advance through the town with weapons at the ready for the least suspicion of resistance. They met with no more than a few isolated shots.

‘The rioters and incendiaries, who had apparently vanished into thin air, lurked around La Barca like souls awaiting the Devil. The ‘Moors’ continued to advance through the town, firing into every balcony and open window, most of which were protected by woollen blankets. Five people died, one of them shot through the keyhole by which she was observing the spectacle. Several people were wounded, but only one seriously, and these were brought to the building which is now the Hotel San Francisco on the Plazuela.

‘Meanwhile, the streets were patrolled and order was restored, Residents were asked to open their windows, and the call ‘¡Abrir, Abrir! was heard all over town. The priests were released from jail and did their best to calm the people.

'The soldiers left at four in the afternoon the same day, having organised patrols of volunteers to mount guard at the most strategic points in the town, such as the belltower of the church, using the few weapons they had. Three days later, new rifles arrived, together with some old revolvers. José Mera remained in Vejer as head of the militia and Antonio Muñoz as head of the Falange.

‘Voluntary and novice guards continued to police Vejer, and as the tragedy faded, regular soldiers often made jokes at their expense. One day, while on watch, the regulars threw a cooking pot into the Plazuela, where the casino once was, and in a panic, the volunteers dispersed the crowd, believing it to be a bomb.

‘A little later, the same volunteers were on guard when they heard voices crying for help. The chief of the guard, believing a severe military emergency to be at hand, mobilised his men, covering the square as far as the street Nuestra Señora de las Olivas. from where the cries came. Investigating a little further, however, they discovered that all the cries came from one window, and were the lament of a woman whose brother had just died.

![]() |

| The Falange maintained authority with a powerful military presence |

‘While the situation gave rise to some comical situations like these, some of the families of the town were overwhelmed by tragedy. Many of the former extremists had been jailed, filling the municipal prison to its limits. Some were shot in subsequent expeditions made by lorry between the outskirts of Chiclana, or along the highway to Medina. Every morning, prisoners' wives took coffee to the jail on Calle de la Fuente only to find that their menfolk had been shot and buried at dawn. They returned to their houses inconsolate and tearful, announcing to their neighbours the sad news. Many died in this way, whose only crime had been ignorance or the recklessness of youth.

‘The nationalist rebels continued their northward march, conquering territories as they went. The first Vejeriegos to be recruited to fight in the Nationalist campaign were enlisted into the ‘Lions of Benamaoma’ battalion in August 1936. On September 11th, an expedition left for Algeciras, encountering its first armed conflict at Manilva. The first Vejeriego to die in action on the Nationalist side was José Castrillón Shelly.'

The Civil War was ‘won’ by the Nationalists in 1939, though many historians believe that Franco deliberately delayed the conquest of Madrid until he had the rest of the country under control. Franco did not need the support of the people. He believed he ruled 'by the will of God'. Over the next three years, many Spanish people would lose their lives in the conflict. However, Republican resistance did not end there, and until well into the 1950s, the ‘Maquis’ guerillas put up a spirited resistance, a topic which I will explore in my next post.

![]() |

| Local youth was indoctrinated with Nationalist ideology. Here seen drilling on the Corredera. |